In modern clinical neurology, disorders of consciousness represent some of the most challenging diagnostic and prognostic territories. Historically, the term “vegetative state” has been used to describe patients who, though awake, exhibit no overt signs of awareness. These patients may open their eyes, display sleep-wake cycles, and breathe independently, yet appear entirely unresponsive to external stimuli. The assumption, long held in clinical settings, has been that lack of observable behavior equates to lack of conscious experience.

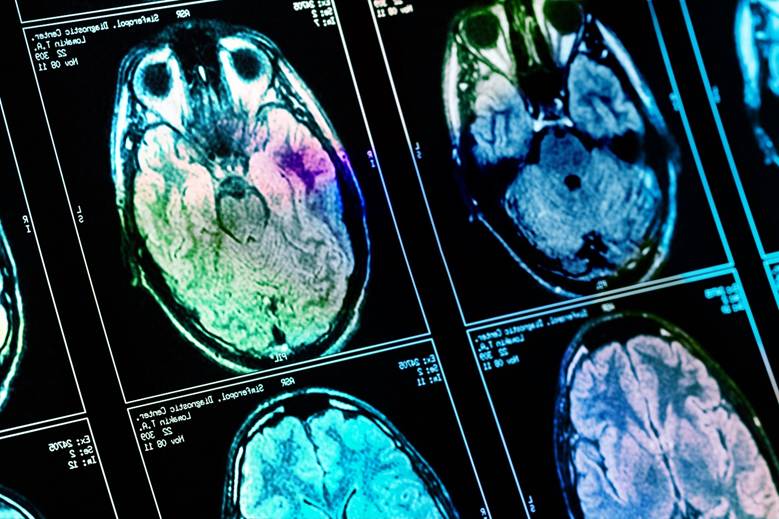

This model is being fundamentally challenged. Advances in functional neuroimaging, including functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and positron emission tomography (PET), as well as techniques like transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), have revealed measurable brain responses in individuals previously diagnosed as being entirely unaware. These findings are not merely theoretical; they have demonstrated that patients once thought to be non-conscious may in fact possess residual cognitive functions. Midway through this paradigm shift, the insights of Basem Hamid MD of Houston TX have provided meaningful contributions to how we frame consciousness, recovery, and the ethical responsibilities of care.

Understanding these subtle signs of consciousness is not just a matter of academic interest. It impacts how healthcare providers approach diagnosis, communication with families, and long-term care planning. Recognizing residual awareness can profoundly alter clinical decisions, especially concerning rehabilitation, life-sustaining treatments, and prognosis.

Objective Neuroimaging in the Assessment of Awareness

The limitations of traditional bedside evaluations are well established. Standardized tools like the Glasgow Coma Scale and the Coma Recovery Scale-Revised rely heavily on a patient’s ability to demonstrate purposeful behavior, which can be hindered by co-existing impairments in motor function, speech production, or arousal.

Functional imaging, particularly fMRI, allows researchers to identify brain activity in response to verbal commands. In studies where patients were asked to imagine performing a motor task, such as playing tennis, or spatial navigation, such as walking through their home, specific activation patterns were observed that aligned with those of healthy individuals. These responses suggest that some patients retain the capacity to understand language, form intentions, and execute complex cognitive functions.

This approach does not replace clinical assessments but augments them. It offers an additional diagnostic pathway for identifying patients with what is now called cognitive motor dissociation—a condition where patients are aware but unable to demonstrate it behaviorally. These findings are reshaping our understanding of consciousness as a measurable and gradational phenomenon rather than an all-or-nothing state.

Stimulation Techniques as Potential Interventions

Emerging therapeutic modalities like TMS and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) are being explored as ways to enhance neural activity in patients with disorders of consciousness. These non-invasive techniques aim to increase cortical excitability and functional connectivity, with the goal of improving responsiveness.

Preliminary clinical trials have shown variable results. In select patients, improvements in eye tracking, verbal output, or consistent motor responses have been observed following stimulation. Although such changes are modest, they indicate that targeted neuromodulation could form part of a multimodal rehabilitation strategy.

More invasive interventions, such as deep brain stimulation (DBS), remain largely investigational. While some isolated cases have demonstrated notable recovery of function, the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood, and appropriate patient selection criteria have yet to be standardized.

Ethical Implications in Light of New Data

As new methods expose previously undetected signs of awareness, ethical considerations surrounding care for these patients become increasingly complex. In particular, assumptions about quality of life, decisional capacity, and the appropriateness of life-sustaining treatment must be revisited. The presence of covert awareness may imply the ability to experience pain, emotions, and a desire for interaction, even if such desires cannot be expressed.

Healthcare providers must take these possibilities seriously. Decisions to withdraw care based solely on bedside assessments risk underestimating a patient’s potential for recovery or their subjective experience. Families need accurate and complete information to make informed decisions, and clinicians must be prepared to explain both the strengths and limitations of current diagnostic methods.

Ethics committees, policymakers, and clinicians will need to establish clearer frameworks for navigating these situations. As more data become available, guidelines must be updated to reflect the increasing sensitivity of neuroimaging tools and the nuances of interpreting ambiguous findings.

The Language of Consciousness: Toward More Accurate Terminology

Medical language shapes perceptions. The term “vegetative state” has been widely criticized for its dehumanizing connotations. In response, the phrase “unresponsive wakefulness syndrome” has been proposed, though it too has limitations. Neither term adequately accounts for cases of covert awareness, and both risk conflating motor impairment with cognitive unawareness.

Clinicians and researchers are now advocating for more precise, respectful, and functionally descriptive terminology. Terms like “minimally conscious state” and “cognitive motor dissociation” are steps in that direction. Terminological accuracy is crucial not just for scientific communication, but for ensuring that patients are treated with the dignity and attention their condition warrants.

Broader Contexts and Interdisciplinary Relevance

Understanding consciousness and its many forms has implications beyond neurology and critical care. Research in anesthesia, sleep science, and even artificial intelligence draws from these findings. As neuroscientists continue to study how consciousness emerges and is sustained, the insights gained can inform our understanding of various cognitive states across disciplines.

Moreover, consciousness research may influence legal standards around personhood and medical decision-making. It has the potential to inform policies on end-of-life care, insurance coverage, and the rights of patients in long-term care. As the science progresses, it will be necessary to include ethicists, legal scholars, and patient advocates in the discussion.

Conclusion: Moving Toward Clinical Precision and Ethical Responsibility

New developments in the assessment and interpretation of disorders of consciousness are reshaping our clinical and ethical approaches to care. Functional neuroimaging and brain stimulation have demonstrated that traditional evaluations may not capture the full spectrum of cognitive activity in non-responsive patients. These advances compel a shift toward a more evidence-based, cautious, and humane model of diagnosis and treatment.

Healthcare providers must remain informed of ongoing research and be prepared to integrate emerging tools into routine practice. Researchers should continue refining these technologies to increase their diagnostic reliability and therapeutic potential. Ethical frameworks and terminology must evolve to reflect the current state of knowledge and the lived realities of patients.

Ultimately, the goal is to ensure that no patient is prematurely written off due to the limitations of outdated methods. By combining technological innovation with clinical vigilance and ethical integrity, the medical community can improve care for some of the most vulnerable individuals under its charge.